There’s more to a tree than you may have thought. Consider the characterizations from a scientist, a philosopher and a poet.

Professor Birgitta Whaley pursues novel quantum computing devices by using advanced probing methods (ie. ultrafast spectroscopy) to resolve the underlying mystery behind a biological molecule’s capacity to concurrently inhabit multiple places, times or energy states in what is called a superposition, in trees.

How is this measured? In an interview with Quanta Magazine, she says she, “measure[s] crisscrossing pulses of laser light with spectrometers to follow the molecular dynamics of biological objects in real time, as measured in quadrillionths of a second.”

The results of these measurements are far more stimulating than the taking. In a video, Professor Whaley elegantly describes how a tree is the most sophisticated nano machine on earth. It’s efficiency for converting radiant energy (sun light in the form of photons) into biomass can only be explained by quantum effects in photosynthesis because its light harvesting efficiency is near perfect. This phenomenon is not a hypothesis. She shows how energy travels over 15-30 nano meters in one nano second in a wave-like pattern that maps to quantum effects. By the way, Albert Einstein famously dismissed quantum effects as, “spooky action at a distance.”

Professor Whaley says Erwin Schrödinger’s bio-physics book “What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell”, published in 1944, contained the first suggestion that quantum physics could be at work in living things. Now that Schrödinger’s theory appears to have been demonstrated to be (at least) partially correct, the question “What’s In A Tree?” becomes a lot more interesting.

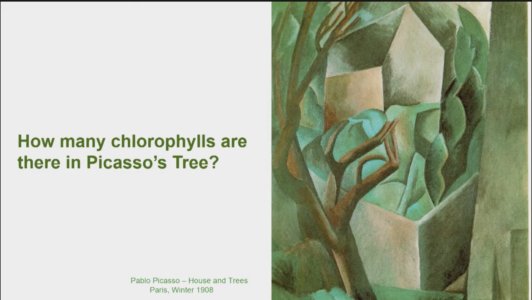

The answer to Professor Whaley’s question (see above) about the quantity of chlorophylls in an adult tree is 140 grams (one third of a pound). So with nothing more than a seed, some sunlight and soil, a tiny amount of chlorophyll can produce a living adult tree of several tons, at the ambient temperatures present on almost any of earth’s moist and dry surfaces. I’m curious as to why she selected a famous artist’s painting to represent a tree. It’s as if she has a reverence for trees that is closer to philosophy than physics. None of Professor Whaley’s tree investigations suggestion the taking of living trees but rather to borrow from the tree’s own inherent qualities to advance human compute tools.

Martin Buber was 20th century philosopher who saw the world in terms of a dialogic principle. His writings reduced the relation between persons, animate objects, and deity to three signifiers: “I”, “You” or “Thou”, and “It.” His studies ranged from philosophical psychology to Jewish mysticism. We can also think about ways the distinction between Buber’s three signifiers applies to a tree because he explored man’s relationship to a tree as an example in his writing.

In his short philosophical essay, I and Thou, Buber describes knowing a tree in a scientific sense as an I-It relation, in which something is treated as an object of dominance, control and exploitation in the same ways people sometimes operate in social situations. He says, “The tree is no impression, no play of my imagination, no value depending on my mood; but it is bodied over against me and has to do with me, as I with it — only in a different way. Let no attempt be made to sap the strength from the meaning of the relation: relation is mutual.” Buber qualifies the I-It mode of knowing as acceptable in the scientific arena so long as it is acknowledged that the full picture of reality is more expansive than the I-It. Buber suggests the center of value should be somewhere between I-It and I-Thou. When he says the relation to the tree is “mutual,” Buber is placing humanity’s relation to nature as a mystical union close to the I-Thou, or that between God and man. He is expressing a dialectic ideal to transform I-It relations closer to the I-Thou or I-You by the changing of the orientation of the self – a leap that requires one’s, “full being.” (Buber is difficult to summarize, so watch this video for a fuller description.)

Where Buber dissects dialogic transformations of the self to improve relationships, Mary Oliver erases any boundaries and in doing so reveals an inner monologue that is a truer and more accessible picture of trees and the self. The mystical union intimated by Buber as a source meaning is fully alive with Oliver’s humanized conversation with trees. She captures, linguistically, how simple light enriches trees (perhaps she knows something about quantum biology?) and extends the reach of imagination by suggesting that a similar simplicity has a spiritual dimension in humans.

Listen to her poem:

In some spooky way, Oliver puts the I-Thou in Buber’s I-It without the slightest acknowledgment of the corrupted essence of our existence that seems to shadow Buber’s deep-thinking methods. That cool ray of photons streaming down through the leaves fuels her clean-burning words, as if she’s doing the thinking for all the three of our subjects. Finally, and just when you think Buber’s abstractions go beyond Pluto, he swings back into orbit with, “But whoever lives only with It, is not a human.”